Levellers

Peace: a word that’s both direct and loaded with meaning. On the surface, it suggests tranquility, evenness, a state of bliss already achieved.

But the word that gives the Levellers’ 11th studio album its title is open to a multitude of interpretations, too. It could be a reference to a disappearing value. It could be a sneering statement of irony. It could be a cry for calm in a crazed world. It could mean whatever you want it to mean.

“It’s an aspirational title,” says Levellers singer/guitarist Mark Chadwick. “We’re searching for peace. I’m not a religious man, but it feels like the devil is walking the earth right now, but that doesn’t mean there’s no hope.”

Peace is the most relevant album to come from 2020. Its 11 electrifying songs are a charged reaction to a world that seems to be teetering on the edge of madness and self-destruction. The environment is buckling under the weight of humanity’s disregard, right-wing demagogues are spreading hatred and fear across supposedly civilised nations, society and culture is trapped in a death spiral that’s playing out in real time across social media.

“The album is about the state of the world and our state of mind,” says bassist Jeremy Cunningham. “It’s the most anxious-sounding record we’ve done in a long time. It’s the way the world is. We’re just reflecting it. It’s an album of now.”

It’s been a long journey to get here. Peace arrived almost eight years since the Brighton band’s last album of original material, 2012’s Static On The Airwaves, though the band – completed by Simon Friend (guitar/vocals), Jon Sevink (fiddle), Charlie Heather (drums) and Matt Savage (keyboards) – have been far from idle. During that time, they toured the world multiple times and released 2018’s acclaimed We The Collective, which featured acoustic versions of several classic Levellers songs.

“That really did spark our musicianship and our confidence,” says Cunningham of We The Collective, which became their highest-charting album in more than two decades, and the subsequent tour. “It energised us when it came to making this new record.”

The last eight years haven’t always been easy. While a string of global crises have played out in the news, there have been more personal traumas and battles to overcome at home.

“The album reflects everything we’ve been through in the last few years, all this weighty stuff,” says Chadwick. “It’s part of the atmosphere of the record. It can’t not be in there.”

All the internal and external turmoil helped give the album a focus. Produced at the band’s own Metway Studios by longtime collaborator Sean Lakeman (“He knows the Levellers better than the Levellers,” says Chadwick), Peace possesses the clarity and directness early Levellers classics such as their 1990 debut album A Weapon Called The Word and its landmark follow-up, Levelling The Land.

“For me, it has elements of that early period of the band, especially in its strength and purpose,” says Chadwick.

“It’s more song-based, it’s chorus-heavy, there’s no messing about,” adds Cunningham. “There’s absolutely no chaff in there.”

That direct approach is evident on jagged, spiralling opening track and first single Food Roof Family, a song that blazes with anger and urgency. Its lyrical concerns are unvarnished and unambiguous, but then now isn’t the time for ambiguity.

“Everybody needs those three things, it doesn’t matter where you’re from,” says Chadwick. “It’s something that we all crave. Why does anybody want more roof than anybody else, or more food than anybody else, or want to kill anybody else’s family. It doesn’t make any sense.”

As ever, the Levellers are unafraid of tackling the big subjects on Peace. The Men Who Would Be King sets its sights on those figures of authority who have taken it upon themselves to reshape the world in their own malign image.

“What makes people think they can control your universe?” says Chadwick. “What arrogance does that take? I don’t like ideologues and I don’t like power-crazed nutcases.

“Their bad decisions are infectious,” adds Cunningham. “They compound things, make them worse.”

Ghosts In The Water address the current climate catastrophe in chillingly poetic terms. “This is not going away, it’s serious,” says Chadwick.” It’s a curse from the earth on us: ‘Look what you’ve done.’ The ghosts will wreak their revenge on us, unless we do something about it.

The political and environmental powder keg hanging over us all can’t help but infuse the sound and atmosphere of Peace, but like all great art it’s equally effective when it focus on humanity and society rather than global political systems.

Albion And Phoenix, featuring Chadwick and Simon Friend sharing vocals and inspired by a squatted brewer named The Phoenix on Brighton’s Albion Hill, is both a celebration of the Levellers’ past and a warning against the suffocating nature of nostalgia. Similarly, the plaintive modern folk of Four Boys Lost – based on the true story of a tragic accident off the coast of a remote Scottish island – packs a massive emotional punch.

“Four guys died, one survived,” says Cunningham, who was inspired to write the latter song after hearing about it from a friend who lived on the island. “That was the sum total of their young male population wiped out in one night. People were there, pulling the bodies of their friends out of the water.”

If that song represents Peace at its most baldly affecting, the Levellers don’t stint on using big choruses and melodies to smuggle through their intent on other tracks. The anthemic Burning Hate Like Fire is a commentary on the cycle of anxiety, negativity and grimness that comes with living in the fast-moving modern world.

“It sounds like a big pop tune until you really start listening to it,” says Cunningham. “Then it’s, ‘That’s a bit uncomfortable.’ It’s quite a subversive song, that one.”

Elsewhere, the Levellers channel the music that inspired them in their youth. The terse but tuneful Our New Days rushes by in a heartbeat. “Two minutes of old fashioned punk rock fury,” laughs Chadwick.

Yet for all the tensions and anxiety that underpins it, Peace is ultimately a hopeful album. It’s apparent in that aspirational title. It’s there, too, in the final line of Our Future, the album’s closing track: “Our future is the only thing worth thinking about,” sings Chadwick, his voice urgent with hope.

“We’re realists, but we’re quite hopeful as well,” says Chadwick. “We believe in positive change, not just moaning about shit.”

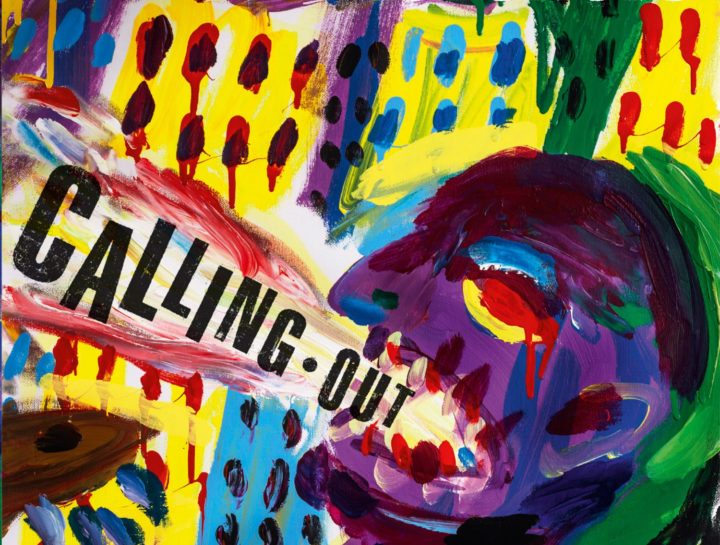

That sense of positivity is brought to life by the album’s striking artwork: a vivid phoenix, painted, like all of the band’s covers, by Jeremy Cunningham.

“The phoenix signifies creation from destruction,” says the bassist. “There’s a lot of bad things in this world right now, but there’s always hope. You’ve got to have hope or you’d go mad.”

The Levellers have always been outsiders, even during that brief period when they found themselves in the mainstream spotlight in the 1990s. The margins are where they belong, and it’s where they’re happiest.

“Without a doubt,” says Cunningham. “We’re a thorn in the side of popular culture.”

But being outsiders doesn’t mean irrelevance. In the 30 years since they announced themselves with A Weapon Called The Word, the Levellers have created their own self-sufficient world, one that includes everything from the Metway Studios to their hugely successful Beautiful Days festival, now in its 18th year. The fire that fuelled them 30 years ago is far from being extinguished. With Peace, that fire burns brighter than ever.