Built in 1923 on the South Side of Chicago as a community savings and loan, the building was purchased by renowned artist Theaster Gates in 2012 and reimagined into a cathedral of Black art; 17,000 square feet housing a one-of-a-kind space for innovation in contemporary art and archival practice.

Stony Island’s collection encompasses a vast array of art and artifacts. Among them are house music legend Frankie Knuckles’ 5,000-deep vinyl collection, a trove of 15,000 books and periodicals donated by the Johnson Publishing Company —publisher of Ebony and Jet magazine — and a collection of “negrobilia” that includes postcards depicting lynching and ash trays sculpted in the images of black children.

While Bailey Rae’s transformation was gradual and remains ongoing, the spark to the sheer enormity of the venue and the witness it pays to Black art and life was immediate. The two-time Grammy winner began writing the songs for her newest release Black Rainbows before she’d even left the building from her first visit in 2017. She continued tinkering with them up until early 2023 saying with a laugh “I finished the last bit of recording the day before we sent it to be mixed. If you give me that amount of time, I will work right up to the last minute, because I’m always thinking of ways I can make it better.”

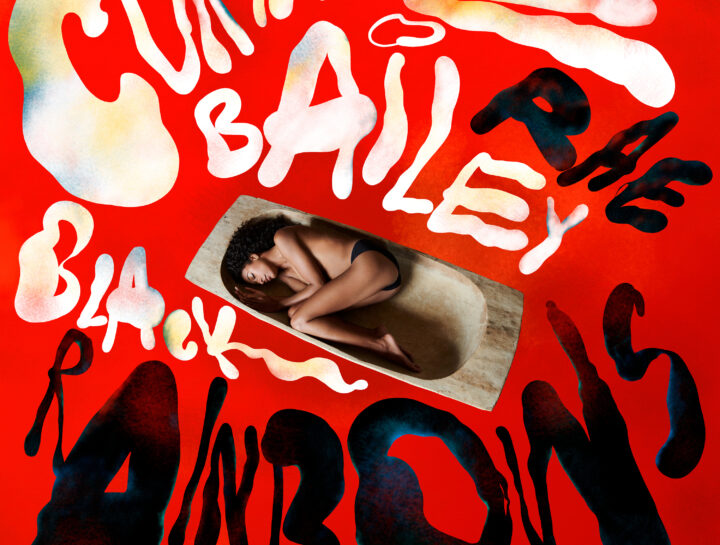

That perfectionism was even more crucial on Black Rainbows, her fourth album, out September 15, given how deeply felt it is.

The 10-track collection—co-produced by Bailey Rae and her long-time creative collaborator Steve Brown—is a testament not only to the stimulating power the Stony Island Arts Bank collection has to push artists to become their highest, most expressive selves but the depth of Bailey Rae’s gifts as a songwriter and vocalist. The spectrum that the Leeds-born artist traverses reveals new elements of her spirit.

The ravaged anger and electric guitar cacophony of ‘Erasure’ gives way to the chilly alien synths and birdsong of ‘Earthlings’. The giddy girl group fizz enlivening ‘New York Transit Queen’ —all handclaps and joyous gang vocals— contrasts with the spare piano balladry of ‘Peach Velvet Sky’. Black Rainbows feels very much like a work of trapeze artistry as Bailey Rae flings herself from song to song, firmly grabbing each successive bar to keep the flow consistent as she sings of beauty queens and the enslaved, churches embedded in the rock of the earth and outer space.

Ultimately, Bailey Rae plans multiple explorations around her Stony Island inspirations, including a dance piece, visual art, books, lectures, and more. As the various projects come together, she is excited for audiences to hear all the colours in the prism of Black Rainbows.

CORINNE REVEALS MORE ABOUT BLACK RAINBOWS

WHEN DID YOU FIRST DISCOVER STONY ISLAND ARTS BANK?

In 2017, I was on tour in Chicago, and I had heard about it, but I was leaving the next day very early. Somehow, my manager invited Theaster to the show and he offered to give me a tour.

There was a sculpture made from the floorboards of a Chicago police station and I thought, “What have these floorboards seen?” Then there was a collection of “negrobilia,” problematic objects from America’s past. There was a Nick Cave Sound Suit hanging up.

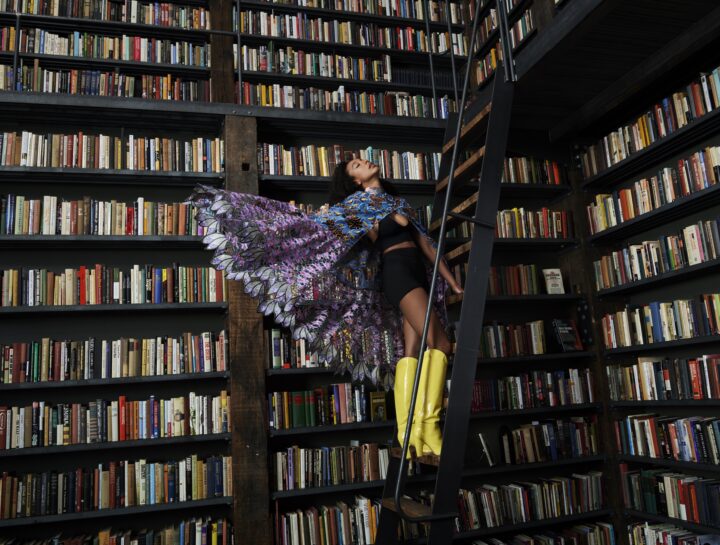

When I first went in the library, the books from the Johnson Publishing Company collection hadn’t been put in order yet and you could look at just one shelf and see books about the Rock Churches of Ethiopia, Mask, Dance since the 1500s, a book of recipes, and a book about the Black pioneers who went west. I love libraries like that where it’s like you’re just putting your hand across, and you go this way and it’s 300 years in the past, this way 2000 years, and this way leads you into the present.

THE ALBUM FEATURING SO MANY DIFFERENT STYLES MIRRORS THE DISPARATE NATURE OF THE COLLECTIONS IN THE ARTS BANK ITSELF. WAS THAT INTENTIONAL OR WAS IT ABOUT LETTING THE SONGS BE WHAT THEY WANTED?

To me it’s tightly focused because it is all in response to these objects in the Arts Bank. I felt like, if that is my golden thread, if that’s my target, then it meant that all the music stuff could just be anything as long as it was coming from those objects. To me, it’s totally cohesive because of where everything came from. But I recognize that in terms of the styles, they are really wide. I wanted it to be like that.

IT WOULD BE GREAT TO HEAR ABOUT SOME OF THE SPECIFIC OBJECTS THAT INSPIRED THE SONGS. WHERE DID OPENER ‘A SPELL, A PRAYER’ COME FROM?

With this story it wasn’t a specific object so much as all of the objects together. There are a lot of narratives of enslaved people held in the building. I was thinking about ancestral pain, about whether the past, present and future could be in a different adjacency. Whether the present could affect or disrupt the past. I thought about notions of freedom and whether it was possible for our enslaved ancestors to have flashes, transcendent moments, of freedom, maybe in the birth of a child, or sexual union, or religious ecstasy.

I thought a lot about the generational handing down of knowledge from one group to another. How we pass on knowledge. I thought about Frankie Knuckles and how he’s remixing music. He’s hearing music from another moment and bringing it to his now and how people are still doing that with his music or the music that was being digitized there, so you’ve got the vinyl turning to digital.

‘ERASURE’ IS A PARTICULARLY GRIPPING SONG WITH ITS FUZZ AND CLATTER AND YOUR INTENSE, ALMOST SCREAMING VOCAL. WHAT DREW THAT OUT OF YOU?

Some of the themes of ‘Erasure’ are concerned with the erasure of Black childhood so I wanted it to be unhinged and witchy, allowing broken down collapsed mental health in. How else do you sing, “They put out lit cigarettes/Down your sweet throat/They fed you to the alligators”?

I saw scores and scores of postcards of children escaping from alligators, and the threat of children being fed to them. Some plantations were surrounded by alligator swamps. I saw what looked like a small sculpture of a boy with his mouth open sitting on a potty. He looks like a toddler who’s really struggling, crying because he’s trying to use the toilet. As a mother, I feel such a huge connection to this boy that’s not a real boy, but it stands in for many children who are in discomfort and needing the love of a mother. But then I looked closer and realized that the potty detaches, and it was an ashtray. People put out cigarettes into the throat of a child. I thought “What kind of world is this where this piece is made for white amusement?”

I also saw a picture in a photography book called Hard Art, about the hard rock scene in DC in the ‘70s and ‘80s. It showed all these rock bands like Bad Brains playing a local housing project in DC. There was this photograph of a band playing, and some in the audience were kind of folding their arms, not quite sure about this music. But there was this little Black girl on the front row, and she’s looking at the lead singer with this expression of pure glee on her face at this rule-breaking noisy music. She’s just enraptured. I thought, “I wish I had seen this photograph when I was screaming in my indie band Helen, and I was the only black girl, not just in the band, but in the room.”

I felt a lot of anger when I was there because I was peeling back a kind of truth that I hadn’t known.

‘NEW YORK TRANSIT QUEEN’ ON THE OTHER HAND IS EBULLIENT AND JOYFUL.

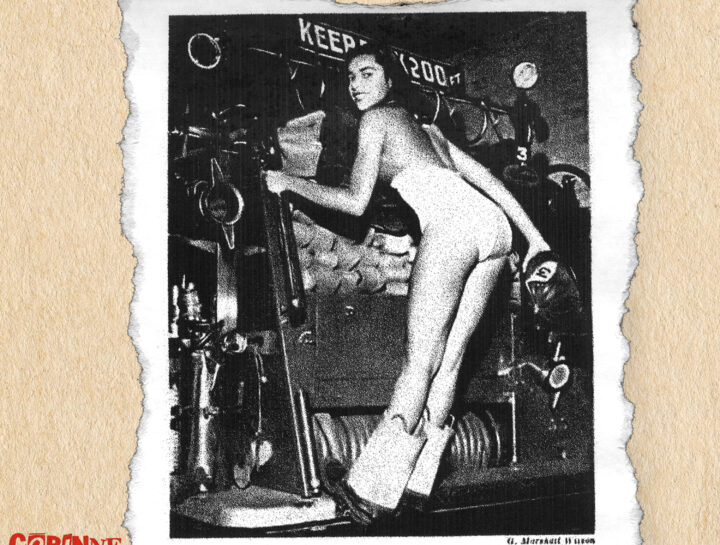

It’s so much fun. I saw a photograph in Ebony magazine of Audrey Smaltz winning the Miss New York Transit pageant. You see her coronation with several girls around her. But the main photograph I love is of Audrey Smaltz who’s still alive (she’s in her 80s!). It’s 1954. She’s in a bathing suit, looking over her shoulder. She’s hanging off the back of a firetruck wearing fireman’s boots rolled down. It’s this sexy, playful cheesecake sort of image.

I’m really used to seeing those sorts of images of someone like Bettie Page, but I haven’t seen it in a Black context before.

Audrey Smaltz’s song became a riot grrrl punk song because she has this playful, hellraiser look in her eye. When I would see these 1950’s cheesecake pictures in the 1990’s they’d be reframed as posters for shows. The sexy or domestic would be reimagined as powerful/tough/sexy/outside of male gaze flyers for all girl band nights. Those images put me in the mind of that and again, my indie band Helen, which sounded like this song.

ANOTHER COLOUR HERE IS THE AUSTERITY OF ‘PEACH VELVET SKY’.

That was the last song I wrote for the record. I was rereading Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, which my Aunt, who lived in the U.S, had sent me in my teens. It is the autobiography of Harriet Jacobs, a young, enslaved woman, who escapes the violence and sexual harassment of her “master” by feigning her flight north. She actually hides in the crawl space above the storeroom of her free grandmother’s house, and she stays there for seven years. This was always a shocking and wild flight of bravery to think about in my childhood. Jacobs bores a loophole so she can see out. She sees her children growing up as they occasionally play around her garret, she sews them clothes by the light of her loophole.

The song is about what the sunset looked like through this aperture. She made a prison for herself, but through that prison she created the conditions for safe escape. It’s such a powerful and incredible story.

THE ALBUM CLOSES WITH THE MAJESTIC, CONTEMPLATIVE, SHIMMERY ‘BEFORE THE THRONE OF THE INVISIBLE GOD’. WHY DID YOU CHOOSE THAT TO CAP IT OFF?

With the record we have been in the celestial, the transcendent, I wanted to end back on the earth, in the rested stillness. At first I thought it would end with ‘Peach Velvet Sky’, but I felt like that song ends with a question. It’s not settled, because you want to know she’s escaped, and you’re not left in the song with fully knowing what the cost of that compression and confinement was.

I discovered this book in the Arts Bank about the rock Churches of Lalibela in Ethiopia. They are ancient churches that are hewn from the rock. The Ethiopian people would look out on a flat, rocky plane and then decide to make a church by digging downwards.

In one of them, there was a picture of a throne they had made. It was recessed into the wall. But they’d also made some steps for God to climb up. And I thought that was really funny that this all-powerful, omnipotent God needed some help getting up the stairs. [Laughs] I thought it was really brilliant and interesting. We’re trying to ideate our concept of the infinite and the divine and all powerful, but we can’t get outside ourselves and what our limitations are.

IN ADDITION TO THE ALBUM, YOU WILL BE WORKING ON OTHER VARIOUS OTHER PROJECTS INSPIRED BY YOUR VISITS TO STONY ISLAND. WHAT DROVE THE DESIRE TO EXPRESS YOURSELF THROUGH ALL OF THESE OTHER ARTISTIC MEDIUMS?

It needs to be all of the other things. The main thing for me is my exposure to the arts bank has been a real transformation in the way that I’ve seen myself. Coming out of having lots of success with my first record —which I’m so grateful of— you can start to feel, especially when you work with major labels, that you have to go on repeating a particular type of pattern: “We want you to make sunny, up tempo, positive songs that also might be about love.” I want to make more than that.

My second record was made after I lost my husband when I was 29 years old. He was 31. That had a massive influence on the stuff that I thought about and that affected that record.

With my third album, I felt this pressure: “You made that more complicated record, but now you need to regain where you were when you had this kind of pop success.” I didn’t have the belief or strength or confidence to say, “No, I’m just going to do exactly what I want.” That’s why it was so amazing encountering the arts bank and Theaster who has all these different practices — artist, lecturer, potter, choir director, business owner — but they’re all him and they’re all necessary.

I’ve given myself that same permission. I can make sunny pop songs about love, which I love to do, and I have a deep connection when I play them. People come up to me afterwards and say a song helped them or they played it while they had a baby or brain surgery. Those things are really important to me. I’m not trying to be disconnected from people. On the contrary, I’m just trying to be myself and follow all of my interests and allow all my fascinations and obsessions to come through in my music in the belief that we are all people, and we all have those connections and questions and interests. We all have layers. I want to explore them all.